R v Caron (2014): Alberta has no Constitutional Obligation to Publish Laws in French

Introduction

On February 21, 2014 the Alberta Court of Appeal ruled that Alberta’s Languages Act is constitutional. The Act allows provincial legislation to be printed in English only.[1] In R v Caron[2], Gilles Caron and Pierre Boutet claimed that certain documents that founded Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta guarantee French language rights in Alberta today. Therefore, they argued that the province must publish its legislation in both English and French. The Court of Appeal rejected this argument, holding that Albertans have never had a constitutional right to bilingual publication as they do for federal legislation.[3] Unless successfully appealed, this decision means that Alberta has no constitutional obligation to publish its laws in French.

Facts

On December 4, 2003 Caron received a $54 traffic ticket for making an unsafe left turn. Likewise, Boutet had been charged with a separate driving offence. The ticket and its governing legislation, the Traffic Safety Act[4] were printed in English only as set out in the Languages Act. Caron and Boutet fought the Act saying it also had to be in French to be constitutional, so the tickets had no effect. Because no provision in the Constitution Act, 1867[5] or Constitution Act, 1982[6] required Alberta to publish its legislation in French, the two looked back into the history of the prairie provinces to find supporting constitutional documents.

Historical Context

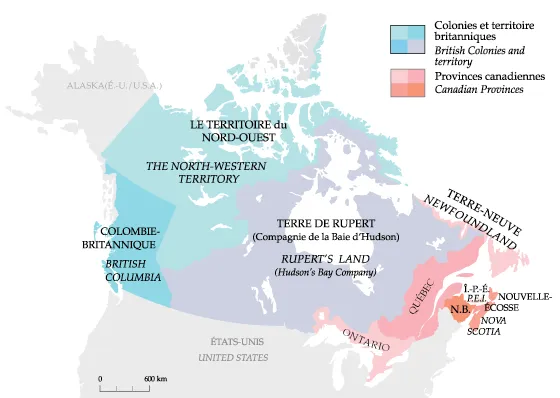

At the time of Confederation, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) still had the charter from Britain to administer Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory. This area was vast, stretching from the shores of the Hudson Bay in present-day Northern Ontario to the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Alberta and north to the Arctic Ocean in present-day Nunavut, Northwest Territories and the Yukon. The most populated area in Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory was the District of Assiniboia on the Red River in present-day Manitoba. The HBC had set up a council to administer the district and pass local rules (ordinances). As early as 1845 the council published ordinances in both English and French, so they could be read and understood by the predominantly French-speaking Metis in the district.

1867 Map of Canada

Image courtesy of Canadian Geographic http://www.canadiangeographic.ca/mapping/historical_maps/1867.asp

Canada recognized the HBC lands as an area for expansion. It included the possibility of admitting Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory into Canada in section 146 of the Constitution Act, 1867.[7]

In an 1867 address, Canada promised Britain that if Rupert’s Land and the Northwest-Western Territory were transferred to it, it would respect the “legal rights” of the area’s inhabitants.[8]

An opportunity to purchase the area came two years later, and Canada eagerly negotiated with Britain, paying £300,000 for the area in what has been called “one of the greatest transfers of territory and sovereignty…conducted as a mere transaction in real estate.”[9]

The Metis in the Red River did not agree with this transfer. During the winter of 1869-70 they resisted surveyors from entering, and drafted lists of rights to join confederation on their own terms. To assure them of Britain’s good intentions, the Governor General issued a Royal Proclamation in 1869 that stated, “on the union with Canada all your civil and religious rights and privileges will be respected.”[10]

Negotiations between the Canadian Government and the Red River leadership led to the 1870 Manitoba Act and provincial status. French language rights and legislative bilingualism were enshrined and constitutionally protected in section 23 of the Act.[11] An 1870 Order, referencing conditions in the 1869 Royal Proclamation, gave to Canada the rest of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory as the renamed North-West Territories. The 1867 address was attached. The North-West Territories Act, 1875 established governance for the Territories, and it was amended in 1877 by the addition of section 110 to require ordinances be printed in both English and French.[12]

In 1905, Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces, but the Alberta Act was silent on language rights.[13] In 1988 the Languages Act declared that the language amendment in the North-West Territories Act did not apply to the Legislature of Alberta, and, as a result, legislation was to be published in English only.

Procedural History

The case was heard in Provincial Court in 2006. Although the trial would have been a routine one under other circumstances, it sat for 89-days so both parties could present their arguments about the constitutional protection of language rights in light of the above documents.[14] In the 2008 decision, the trial judge ruled in favour of Caron and Boutet, clearing them of the traffic charges. Based on the expert testimony and historical context, the trial judge found the Royal Proclamation had constitutional status. It was a guarantee required for the peoples of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory to join Canada. Since the Proclamation formed part of the 1870 Order adding (annexing) the North-West Territories to Canada, there was a constitutional duty for Alberta to publish its legislation in both languages.

The Alberta Government appealed the decision to the Court of Queen’s Bench, where it was overturned. The Court recognized that there was a statutory right to French-language publication in the North-West before Canada bought and annexed it, but the documents in evidence did not demonstrate that this right had been given a constitutional status. Caron and Boutet then appealed this decision to the Alberta Court of Appeal.

Issues in front of the Court of Appeal

(1) Was there a right to the publication of legislation in French prior to the annexation of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory to Canada? and

(2) Was that right entrenched constitutionally at the time of annexation?

Decision

The Alberta Court of Appeal wrote two judgments, but agreed on the main issue: there is no constitutional right to French-language legislation in Alberta.

Justices Rowbotham and O’Brien answered the above questions in the negative. Justice Slatter wrote a supporting decision, but dismissed the appeal based on the binding authority in R v Mercure.[15]

Analysis

Issue 1: Rights to bilingual publication prior to Annexation

The court found that, with the exception of the District of Assiniboia, no pre-existing right to legislation published in French in Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory existed before annexation. Since the District was a defined geographical area and the ordinances were for local matters, the Court could find no evidence or reason why this right would have been extended outside of the District. Whether it was a statutory right to French-language publication, or a mere policy, it gained constitutional status in Manitoba in the Manitoba Act, but nowhere else.

Issue 2: Entrenchment

The court also considered if any of the documents submitted by Caron and Boutet from the period 1867 to 1870 entrenched French language rights at the time of annexation.

Caron and Boutet’s case for entrenchment rested primarily on the 1869 Royal Proclamation. They argued that once Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were transferred to Canada by the 1870 Order, the terms in the Royal Proclamation including the guarantee that civil rights would be respected reached constitutional status. ‘Civil rights,’ in their view, included language rights.

The Court rejected their arguments, noting that they did not “reflect the historical realities at the time.”[16] The Royal Proclamation was not a constitutional document but a political one, and, there was nothing in the 1870 Order indicating Parliament wanted to entrench language rights. Since Parliament had expressly constitutionalized rights to French-language publication in the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Manitoba Act, it certainly knew how to do it. The Court stated that the lack of express reference to language rights in the Proclamation or Order was “an insurmountable barrier” to the case[17] especially since these rights were not entrenched in the Alberta Act.

Justice Slatter made a few additional points. He noted that the 1869 Proclamation did not appear in the Constitution Act, 1982’s Schedule as one of the constitutional documents that included entrenched rights. And, even if the Proclamation protected language rights in some way, royal proclamations can be overridden by subsequent acts of Parliament.

The Court also rejected the appellant’s minor arguments:

- The Metis’ list of rights (including French language publication rights for the whole Northwest) must have been entrenched to get the inhabitants to join Canada. The Court responded that if this were so, the Manitoba Act would not have been needed; and

- Canada’s 1867 Address, where it promised to respect the ‘legal rights’ of the inhabitants of Rupert’s Land and the Northwest included language rights. However, the court interpreted the Address as a promise that government would follow the rule of law in annexation. Since entrenchment was so out-of-the ordinary in that time period, if Parliament intended to entrench those rights in the Address, there would have been explicit reference to it.

The Binding Authority of Mercure

R v Mercure was a similar case where Mercure was charged with speeding under the Saskatchewan Vehicles Act. Citing section 110 of the North-West Territories Act, he applied to have his trial delayed until the Act was published in French and the trial could be conducted solely in French. The Provincial Court refused his application, the trial was conducted in English, and he was convicted. The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) dismissed his appeal, ruling that section 110 had no constitutional force and would only continue in the province until amended.

According to Mercure, the Alberta Act amended the North-West Territories Act in Alberta. But Caron and Boutet argued the Court did not have to follow this precedent because Caron presented new historical documentation not considered in Mercure.

The Court reviewed the SCC’s guidelines from Canada (Attorney General) v Bedford[18] that describes when a lower court does not have to follow the precedent established in a constitutional case. It found that none of the criteria were met, so it could not set aside the binding authority of Mercure:

- No new legal issue surfaced as a consequence of significant developments in the law. The legal issue in Caron is the same as in Mercure;

- No significant change in the circumstances occurred that fundamentally shifted the parameters of the debate. Alberta’s preference for English-language publication had not changed; and

- No significant change in the evidence happened that could fundamentally shift the parameters of the debate. The appellants merely presented a greater amount of the type of evidence considered in Mercure.

Significance of the Ruling

While Franco-Albertans still have a right to federal legislation published in French, this ruling determines that they do not have the same rights to provincial legislation. And because Caron settles the issue in all of the former Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory, it settles the issue for present-day Saskatchewan and Northern Ontario as well.

The appellants are not satisfied with the ruling, believing the weight of history is on their side and that they have a constitutional right to be served in French in Alberta by the provincial government. If the SCC agrees to hear their appeal, Caron and Boutet will carry it forward. Caron will fight the decision because as he told the Canadian Press, “I would like this government to acknowledge they have constitutional duties … they have a duty to serve the French community in a legal way.”[19]

[1] Languages Act, RSA 2000, c L-6.

[2] R v Caron, 2014 ABCA 71 .

[3] See Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3, s 133, reprinted in RSC 1985, App II, No 5.

[4] Traffic Safety Act, RSA 2000, c T-6.

[5] Supra note 3.

[6] Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c11.

[7] Supra note 3 at s 146.

[8] Rupert’s Land and North-Western Territory Order (UK), 23 June 1870 reprinted in RSC 1985, App II, No 9 [1870 Order].

[9] WL Morton, Manitoba: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957) at 117.

[10] Sir John Young, Governor General of Canada, Proclamation, 1870, Session Papers, No 12, (1870) at 43.

[11] Manitoba Act, 1870, 33 Vict, c 2, s 23.

[12] North-West Territories Act, 1875, SC 1875, c 49.

[13] Alberta Act, SC 1905, c 3.

[14] Natasha Dube “Language Rights in Alberta - R v Caron,” online: Centre for Constitutional Studies <http:/www.ualawccsprod.srv.ualberta.ca/ccs>.

[15] R v Mercure [1988] 1 SCR 234.

[16] Caron, supra note 2 at para 51.

[17] Ibid, supra note 2 at para 52.

[18] Canada (Attorney General) v Bedford, 2013 SCC 72.

[19] “Alberta’s Laws Don’t Have To Be Written In French and English: Top Court” Canadian Press (21 February 2014) online: Huffington Post.