By Stephen Raitz (CCS Summer Student, 3L UAlberta Law)

Note: This article was completed in August 2023, before the release of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Impact Assessment Act Reference.

Introduction

The Impact Assessment Act (IAA) is a piece of federal legislation that sets out processes for federal oversight of projects that impact the environment in Canada.[1] Though this sounds mundane, the IAA has the potential to have a significant effect on Canadians across the country. For example, it applies to projects that cause noise or pollution, and projects that extract the natural resources and energy that we use in our daily lives (including “mega-projects” like the development of mines, dams, or highways).[2]

In March 2023, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) heard an appeal regarding the constitutionality of the IAA.[3] The Alberta Court of Appeal (ABCA) had previously ruled that the IAA was ultra vires the federal government’s authority, which means that the feds lacked the constitutional power to pass it.[4] The SCC’s forthcoming decision on appeal will have important implications for the federal government’s role in environmental regulation and management. If the SCC finds that the IAA is valid, then the federal government can continue to exercise considerable oversight of large development projects across Canada. If it does the opposite, the federal government may be sent back to the drawing board.

Federalism Analysis

To determine if a piece of legislation is within federal powers, courts begin by considering the pith and substance of the law.[5] Another way of describing this is “the basic purpose and effect of the law,” or the essential character of the law.[6] To evaluate this, the courts consider an array of factors, including a law’s contents, the process of passing it, and its legal and practical effects.[7] This is known as the “characterization” stage of federalism analysis.

After defining the pith and substance of a law, the court will then determine whether the pith and substance falls underneath a head of power for the level of government that enacted it. This is called the “classification” stage of the analysis. If the legislation is within one of the enacting government’s heads of power (listed in the Constitution Act, 1867), it is valid. If it is not, it is not valid and can be struck down by the court. Striking the legislation down means it is no longer in force.[8] The court could also trim the unconstitutional parts of the law and/or add parts to the law to make it constitutional, thereby allowing it to remain in force.[9]

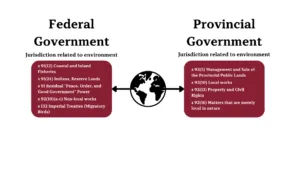

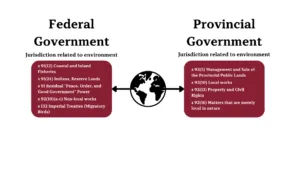

This analysis is particularly complicated where the law at issue is an environmental regulation. In the past, the Supreme Court has described the environment as “too diffuse a topic to be assigned by the Constitution exclusively to one level of government.”[10] This is because aspects of many areas of jurisdiction at either level of government have an environmental angle, as the diagram below indicates.

Because the IAA regulates the environment, it is prone to these difficulties. Certain provisions of the IAA very clearly direct for assessment of a development project’s impact on matters under federal jurisdiction (fisheries, navigable waters, birds),[11] but others are less clearly couched under an area of federal jurisdiction (social and economic impacts of projects).[12] It is therefore a very complicated and multi-faceted case.

Understanding the Main Issues

In what follows, some of the key issues are reviewed from the perspective of the appellant (the federal government) and the respondent (the Alberta government). However, many other issues were raised by these parties that are not covered in this article.

Additionally, interveners participated in the SCC hearings, including several other provinces[13] and a range of non-governmental organizations, such as the World Wildlife Fund Canada, Eco-justice, several First Nations, the Canadian Tax-payers Federation, and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. They also raised other issues not covered in this article.

The Federal Government

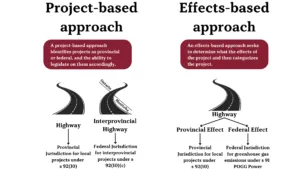

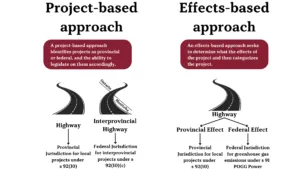

As the appealing party, the federal government focused on critiquing the ABCA decision and asserting that the IAA is constitutional. In their factum, they claimed that the ABCA improperly took a project-based approach as opposed to an effects-based approach to understanding the IAA.[14] The idea of project-based and effects-based approaches is clarified in the diagram below.

The federal government also asserted that the ABCA’s approach was inconsistent with the existing case law that favours a co-operative approach to federalism and shared federal-provincial jurisdiction over the environment. The idea of co-operative federalism envisions provincial and federal governments working collaboratively to achieve mutual goals, rejecting a strict approach to defining the powers of each level of government.[15] Applied, this approach often allows overlap between provincial and federal laws.[16]

Above all, the federal government states that the ABCA was wrong to have dismissed federal jurisdiction to regulate the effects that development projects have on federally regulated matters (e.g. fisheries).[17] Relatedly, they also asserted that the ABCA interpreted the province’s ability to regulate natural resources under 92A too broadly.[18]

The Alberta Government

Alberta took the position that the IAA is unconstitutional, describing it as a “sweeping regime” that does not fit under any federal head of power.[19] To them, the IAA treats provinces as “subordinate levels of government” and not equals within Canada’s federal constitutional system.[20] Some of Alberta’s specific concerns with the IAA include that:

1) Even if the federal government can validly regulate under a federal head of power, they may deny the project based on grounds beyond that federal head of power.[21] For example, Alberta explained that the IAA could allow the federal government to assess a project under its fisheries power (section 91(12) of the Constitution Act, 1867), but ultimately make a decision based on a litany of other factors, including broad public interest considerations.[22]

2) The IAA is focused on regulating physical activities themselves and not their effects due to the comprehensiveness of the regulatory regime, in that section 64 of the IAA allows the feds to place conditions on and monitor relevant projects.[23] To Alberta, this means the IAA extends into and undermines areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, including natural resource projects and electricity generation facilities.

To summarize, Alberta’s viewpoint is that the IAA is a “Trojan horse,” which goes far beyond regulating effects of large projects on matters within federal jurisdiction and invades areas of provincial jurisdiction.[24]

Conclusions: Is the IAA Really a Trojan Horse?

The federal expansion of some facets of the environmental impact assessment process does not necessarily mean that the IAA is a Trojan horse galloping unconstitutionally into provincial areas of jurisdiction. Rather, one may argue that prior (more minimal) federal approaches to environmental impact assessment were examples of “federal deference for provincial preference,” meaning that the federal government opted not to regulate in the past — despite having constitutional jurisdiction to do so — because they deferred to the provinces in these areas.[25] However, Alberta’s submissions raise important questions that could result in the IAA receiving a bit of a trim, at the very least. For example:

Question 1: How far can the federal government go with its POGG powers?

The federal government’s power to make laws for the “peace, order and good government of Canada” (or POGG for short) has been used to uphold environmental regulations in the past. How far does this power allow the feds to go, though, in regulating major projects that have interprovincial impacts?[26]

Question 2: Can the federal government assess under one power, but decide under another?

Alberta’s concern that an assessment initiated under the guise of something like the fisheries power, but decided based on other public interest considerations, presents the Court with the opportunity to finesse its direction provided over thirty years ago in Friends of Old Man River. There, the Court said that environmental assessment can be broad and may consider potential consequences for “a community's livelihood, health and other social matters from environmental change.”[27] Presumably, though, there’s a limit to the role that these factors can play. In this regard, Alberta highlighted other parts of the Friends of Old Man River decision, which suggested that the scoping of the assessment will depend on what federal head of power is being relied on.[28]

***

To conclude, federal attempts to regulate environmental impacts are not necessarily Trojan horses seeking to invade provincial jurisdiction. Engaging the counter-factual is vital here, as Greckol J does in her dissent at the ABCA.[29] As she suggests, the province could validly say “no” to a major project under section 92(10) of the Constitution (local works and undertakings), while the feds could say “yes” to the same major project under section 91(12) due to a lack of negative impacts on fisheries or other matters within federal jurisdiction. In this scenario, the province would not have stymied the federal government’s ability to say “yes” to the project. Rather, the federal government’s approval is simply insufficient in making the project move forward based on environmental considerations.

That said, it is worth reiterating that the heads of power being relied on by the federal government may support varying scales of intrusion into areas of provincial jurisdiction.[30] If the Court finds that the power being relied on does not support such broad federal intervention, and if it is possible to read down the legislation in those areas, the SCC could try to give the law a trim to better reflect the scope of those heads of power. Or, if the Court embraces broader acceptance of Alberta’s position — that the federal law is truly a “Trojan horse” that massively intrudes into provincial jurisdiction — it could also end up taking the IAA or substantial parts of it to the glue factory.

[1] Impact Assessment Act, SC 2019, c 28, s 1 [IAA].

[2] David V Wright, The New Federal Impact Assessment Act: Implications for Canadian Energy Projects, 2021 59-1 Alberta L Rev 67 at 72.

[3] Elise von Scheel, “Supreme Court examining controversial environmental assessment law this week”, CBC News Calgary, March 21, 2023.

[4] Reference re Impact Assessment Act, 2022 ABCA 165 [ABCA].

[5] Peter W Hogg & Wade Wright, Constitutional Law of Canada, 5th ed (Toronto: Thomson Reuters Canada) ch 15, § 15:4–5.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] R v Big M Drug Mart, [1985] 1 SCR 295 at 355-356, 18 DLR (4th) 321.

[9] R v Smith, 2015 SCC 34 at para 31; Schachter v Canada, [1992] 2 SCR 679, 93 DLR (4th) 1.

[10] Friends of Oldman River Society v Canada, [1992] 1 SCR 3, 63, 64, 70 (FORS); POGG, 5th edition 2022 (30:31)) [FORS].

[11] IAA, s 2.

[12] IAA, s 22.

[13] This includes Ontario, Manitoba, NB, and Quebec. BC also intervened and proposed a different approach, which supported allowing the federal government to assess projects, but not to have ultimate approval or denial powers over whether a project proceeds.

[14] Appellant Factum, paras 1-5.

[15] Eric M Adams, “Judging the Limits of Cooperative Federalism” (2016) 76 SCLR (2nd); Quebec (AG) v Canada (AG), 2015 SCC 14 at para 17 .

[16] Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44 at para 149.

[17] Appellant factum, paras 32, 51-56.

[18] Appellant factum, paras 143-148.

[19] Respondent factum, para 14.

[20] Respondent factum, para 22.

[21] Respondent factum, paras 76-77.

[22] Respondent factum, para 77.

[23] Respondent factum, paras 108-112.

[24] Respondent factum, paras 145-146, citing FORS at 71-72.

[25] Marie-Ann Bowden and Martin Olszynski, “Old Puzzle, New Pieces Red Chris and Vanadium and the Future of Federal Environmental Assessment” 2011 89-2 Canadian Bar Review 445 at 480; William R MacKay, “Canadian Federalism and the Environment: The Literature” (2004) 17 Geo Int’l L Rev 25 at 34.

[26] R v Crown Zellerbach Canada Ltd, [1988] 1 SCR 401 at 417 and 438; Interprovincial Co-operatives Ltd et al v R, [1976] 1 SCR 477 at 513-514 and 520.

[27] FORS at para 37.

[28] FORS at 67.

[29] ABCA at para 758.

[30] FORS at 67.